I don't know what was worse when I woke up, the headache or the smell. I was sprawled on one of the beds in the salubrious Safwan Hotel. I had a vague memory of getting back to the hotel. Then I realised that Sami had arranged to take us to his farm today for an all-day picnic. Sami is a warm, hospitable guy, but he doesn't half turn the screws when he wants company.

Staggering down to the reception, I bumped into Grace. Sam was still in bed, moaning off the scotch little by little. They were not going to Sami's farm. I also had an excuse - today was the day I was going to Damascus, the jewel in the crown of my trip. I had to get there and unless Sami could get me back to the hotel or bus station by 17:00, no sale.

13:00 rolls around and as arranged, Sami pulls up, honks, gets out, comes in and sits down.

"Let's go," he said.

"Yeah," I replied. "About that..."

Grace begged off because Sam was still in bed, performing a full Camille. I explained that unless he promised to have me back by 17:00, I'd turn into a pumpkin. Sami cajoled, requested, demanded, insisted, suggested and generally pulled as many strings as he could but in the end he told me that if we went to his farm I wouldn't be back until at least 22:00. Ergo, no farm for me. Sami and I exchanged numbers and he fish-eyed me and Grace closely before leaving without us. I got the impression that he was disappointed.

Grace and I went to arouse Sam from his stupour only to find him in fine fettle, ready to take on the world as long as the world did not include Sami's farm. The three of us slunk into the centre of Lattakia, studiously avoiding Sami's haunts, and surreptitiously enjoyed a wholesome Syrian breakfast of shwarma and garlic sauce. As we ate, who should arrive out of nowhere but Captain Libya, fresh off the bus from Lebanon! He and his new companion, a Syrian student named Lauron, ate and then we all repaired to a Corniche tea house to play some crackgammon and drink chai khameer, the same as normal tea but served with way more sugar and without the tea bag.

I again lost track of time while playing and realised that I would be hard pressed to catch the 17:00 bus to Damascus, which takes four hours. I hurried back to the Safwan, paid Mohammed, said goodbye to the crazy uncle and the degenerate dwarf pervert and was kindly escorted by CL and Lauron to the bus station, where I got my ticket and was firmly ensconced on the 18:00 bus. CL assured me that when I got to Damascus, all I had to do was go to the Methat Pasha main drag and stumble into one of the numerous budget hotels he said awaited me there.

The bus ride to Damascus passed without incident, apart from the presence of the first and only Arab body-builders I have ever seen, two of them, necks like engine blocks, wider than their seats, smoking cigarettes that looked like matchsticks in their sausage-fingered hands. Ridiculous.

I arrived at the Damascus bus station and, luckily forewarned by my trusty Lonely Planet, managed to get a taxi to the Old City for the correct price (50-ish Syrian) as opposed to the taxi scumbag price (200 Syrian). All it took was one honest cabbie who happily put on the meter without me having to ask and even insisted that I drink his cup of tea that jiggled tantalisingly in the cup holder. As we approached the Old City, the streets became more and more narrow, the buildings more and more decrepit, until eventually we were stuck in a traffic jam caused by a road built for horses that had been double- and triple-parked upon until only single file traffic was possible and even then exceedingly difficult. I paid my cabbie, strapped on my gear and headed for Methat Pasha, the main street of the Old City, by day crowded with hawkers and shopkeepers, by night deserted and unlit, eerie in the absence of all noise. I asked a guy wearing a death's head t-shirt for directions. He walked me there. After a few paces, I noticed that he was staring at my hair and beard. He caught my eye.

"Metal?" he asked.

I was momentarily baffled. By way of explanation, he threw up the horns. Awesome. He told me there was metal to be found in Damascus. I looked but never found. His name was, of course, Mohammed. He gave me his number and left me at the start of Pasha street. It was enormous, a huge vaulted ceiling covering what by day is one of the oldest and busiest bazaars in the world. I walked along, seeing no lights and, more importantly, no budget hotels. I came to the end of the street, which degenerated from stately shops and covered roof to piles of rubble in the middle of the road and old houses leaning against each other and groaning like drunks. I asked a group of three guys if they knew where I could find a cheap hotel. In true Syrian style, they insisted on accompanying me for the next forty minutes, tramping around the Old City, looking for a place to stay. One of them was tall, thin and quiet. The talkative one was a sound recordist for Syrian television. The third was dressed all in denim with a centre parting to his hair and a dangerously rakish moustache. He looked like an Arabic Douglas Fairbanks.

They walked with me for ages until we found the ominously named Shahbandar Palace Hotel. I seriously doubted if a hotel with the word "palace" in the name would be in my price range. We rang the buzzer. A slim, nattily dressed guy of about my age answered the door. He spoke excellent English. This place was going to be expensive. I asked how much for the cheapest room.

"120 dollars," he answered.

Shit.

"Is there anywhere cheaper?"

He held up a finger, took out his mobile, made a call, chatted in Arabic for a few moments and then hung up.

"Is 30 dollars alright?"

"That's still way too much," I said apologetically, feeling like an abject hobo surrounded by all these helpful guys.

The guy, whose name was Ammar (his nickname was Mac), made another phone call. He talked, listened, talked again and hung up.

"Okay," he said. "You can stay with me."

"What?"

He spoke to the three guys accompanying me in Arabic. Then he turned back to me.

"They will take you to the internet cafe where my roommate is. He will let you in. I'm sorry but he doesn't speak English. Is that okay?"

I was dumbfounded. I knew the Syrians were nice but this was the absolute limit.

"Are you sure?" I asked, still expecting some sort of joke.

"I'll see you at midnight," Ammar said. "Now go take a shower and relax."

The three guys walked me to the internet cafe to meet Syaman, Ammar's roommate, a Syrian Kurd. As they walked, the Arabic Douglas Fairbanks turned to me and said something that, in the moody lighting from the sparse streetlamps, with the sounds of the Old City murmuring around us, the smells of the warm, humid Middle Eastern night, really caught me off guard and seemed to be more meaningful than I'm sure it was intended to be. He looked me square in the eyes.

"Your mother really loves you," he said.

I froze for a moment and then kept moving. I'm sure it's just a phrase he translated in his head from the Arabic, something they say whenever someone has a stroke of luck, but in context it felt like much more than that. I smiled at him and nodded.

"I'm sure she does," I answered.

We met Syaman at the internet cafe, my three friends said goodbye and Syaman and I walked the five minutes or so to their apartment. Ammar's apartment was one room rented in a shared house. The family that owns the house lives on the ground floor. On the second floor are four bedrooms all rented to expatriates, apart from Ammar. Ammar's room was about eight feet by twelve feet and in it were two single beds. His regular flatmate, a German archaeologist, was away on a dig. Syaman was crashing there for the fifteen or so weeks that the German was away. Syaman was a dark, broad guy with a ready, easy smile and the snazzy dress sense I had come to expect from the Syrians. They are a people that are always dressed formally. Even if they live in a dirt-floored shack, they have at least two sets of formal clothes that they wear out of doors. Syaman taught me to count from 1 to 6 in Kurdish and also taught me the word for "good", which is bash. Zar bash means very good. We communicated in a haphazard manner for about half an hour and then I took a shower. The facilities are shared between the rooms - a common kitchen and a shower room with a Western toilet. The roof of the house is an open terrace with the rooms built in a bungalow style around the square rooftop.

After my shower, I returned to the room to find Ammar back from work. He asked how I was settling in. I thanked him profusely and he interrupted me.

"It makes me angry when you say thank you," he said. "Stop it."

I told him I just didn't know how else to express gratitude. Ammar shrugged.

"This is how we do things here. Maybe one day if I am in London I can stay with you in your home."

I told him it would be my pleasure. He grinned and asked if I was hungry. Before I could protest, Syaman ran off and returned ten minutes later with a pizza, three shwarmas and a bag of soft drinks. They asked if I wanted a beer. I declined. We ate our shwarma and shared the pizza. Ammar asked me about London and what I thought about Syria. He told me about his job and his life. He was from Qamishli, the border town with Turkey. He worked as the night receptionist at the Shahbandar and he had just earlier that day secured himself a two year contract in Dubai at the Palms resort as the reservations manager. At the Shahbandar, a hotel that charges $120 a night for a single room, Ammar made $400 a month. This was very good for Syria, he told me. At the Palms, he would make $1500 a month with accommodation included as a perk of the job. He was very excited about the trip. With his half of the rent being $100 a month, he was currently living on $300 a month, a princely sum for the average Syrian. While I stayed with him, he refused to allow me to pay for anything, even if I tried to sneak. When we went to the internet cafe, he paid. Both Syaman and Ammar, like all Syrians, were smokers, but when they found out I didn't smoke they both smoked outside without a word. I told Ammar that he could smoke inside - after all, it was his place. He told me that if I didn't smoke it would be rude to smoke around me indoors. Syaman agreed and they both took turns smoking on the terrace for the whole time I stayed there. They didn't even smoke in the room when I was out, just so that the room wouldn't smell. When I told Ammar that I have very good friends in London who smoke around me even though they know that I don't and that it aggravates my asthma, he was shocked.

"Why would they do that?" he asked, seriously at a loss. "That's a horrible thing to do to a friend!"

The level of hospitality I enjoyed with Ammar and Syaman was overwhelming.

I got a text from CL asking me where I was staying so he could meet me there the next day. Ammar asked about the text, I explained and Ammar insisted that CL come stay with us at his place. I started setting up my sleeping bag and he asked me what I was doing. I told him I had an air mattress and would be fine on the floor. He asked why I wanted to sleep on the floor. I pointed out that there were two beds and three of us. He told me he and Syaman would share one bed and I would have the other one. I said that that was ridiculous - I couldn't take a bed to myself if my hosts were sharing. He told me that I could sleep on the floor if I wanted but the bed would remain empty on principle even if I didn't take it.

We chatted about life and travel for another hour or so and then I started to doze off. I apologised but Ammar told me to go to sleep and he and Syaman would go to the internet cafe so as not to keep me awake with their talking. My protests were weakened by the fact that I was already basically asleep. After much moral debate, I slept in the bed. And I slept very well.

Wednesday 28 May 2008

Sunday 25 May 2008

Day 19: Lattakia - Be our guest, be our guest

So I didn't go to Damascus today as I planned. Instead I ended up teaching Sam and Grace, two young travellers from Britain via the Netherlands, how to play crackgammon. Then the monkey was on my back and we sat in the local tea house playing all afternoon.

In the morning, before heading out, Mohammed's crazy uncle had a visit from his dentist. Not just any dentist. This guy was a gypsy dentist who carried his surgery gear around in a black leather satchel. He was re-cementing Mohammed's uncle's front teeth, which are fakes. This is what a Syrian gypsy dentist and his patient look like, by the way.

Lattakia worked its magic on me slowly. The sea air, the laidback atmosphere, the cheerful people, all of these things worm their way into one's affections until plans for onward travel take on a distasteful, unpleasant quality. Why would I want to sit on a bus for hours and then fight through the streets of Damascus looking for a place to sleep? I'm sitting in the sun, the sea breeze is cooling my heels and I have unlimited games of crackgammon stretching ahead of me like the soothing dunes of the Sahara. I had been sucked into the Black Hole of Lattakia and I was Ernest Borgnine.

As we sat at the cafe, playing away, a man wearing glasses and sporting quite pronounced but not altogether unpleasant teeth strode purposefully up to the table, looked us over cursorily and announced "My name is Sami. You will all be my guests for dinner tonight." That was how he introduced himself. Sami went on to explain that he was a local farmer and would be honoured if we would join him, his wife and his wife's mother for an evening of traditional Syrian food and music at the local swanky hotel, Al-Cazino. Of course we accepted. Over the course of the evening, however, it became increasingly clear to me that if Sami was a farmer, I was Jesus.

Sam and Grace moved to another table to play each other and Sami joined me at the board. He ordered tea for us both and then proceeded to hand me my ass in a merciless fashion. I learned a great deal from playing him. He called his wife several times and eventually she arrived, driving his car. She was wearing make-up, tight jeans and a leopard print top. Their Filipino maid was sitting in the front with them. Sam, Grace and I piled into the back.

At their apartment, Sam, Grace and I were offered fruit, candy and nuts while Sami and his wife bustled about getting ready. Their Filipino maid fetched drinks and, when Sami and his wife were not in the room, happily answered questions about how she ended up in Syria. She told us that lots of Filipinos work in the Arab world as domestics. Her agency in the Phillippines sent her to Lebanon, which she hated, and then offered her the choice of going back to Lebanon or to Syria. She chose Syria. I asked her if she liked it. She waited pointedly until Sami's wife left the room and then said that it was better than Lebanon, but with a look on her face that said she would much rather be somewhere else entirely.

Sami and his wife were a very progressive couple. They eschewed traditional dress and formality in favour of very Western habits.  Sami happily talked to us while wearing his towel straight out of the shower. He and his wife had a playfulness that I had never seen in an Arab country before. His wife showed us stacks of photo albums, including their wedding pictures, in which she is sporting quite the quiff and wearing what would be classed as a racy number even by Western standards.

Sami happily talked to us while wearing his towel straight out of the shower. He and his wife had a playfulness that I had never seen in an Arab country before. His wife showed us stacks of photo albums, including their wedding pictures, in which she is sporting quite the quiff and wearing what would be classed as a racy number even by Western standards.

Sami's mother-in-law arrived with her Filipino maid. Apparently they are all the rage in Lattaki right now. Mother-in-law was a really tough audience. She spoke no English and glared at me in that tight-lipped manner that older women have that gives you the impression that they've seen through you in some way even if they haven't. For a while I was sure she had smelled Jew on me, but I was thrown a lifeline that I pounced on to great effect.  Sami was watching the news and the Future party was mentioned. I asked him who he supported in Lebanon. He said that he was for Hezbollah, 100%. He also said that I would be hard pressed to find anyone in Syria who didn't take Hezbollah's side. He said that many, including himself, had written Hariri off as a Western puppet. I immediately whipped out my camera and showed him the pictures of me in Baalbek, at the gift shop, in the mosque. I told him about my meeting with Abou Yasser and Fatah al-Intifada. He translated for his mother-in-law. She broke into a veritable sunstorm of smiles. Problem solved. I was in. I was one of the family.

Sami was watching the news and the Future party was mentioned. I asked him who he supported in Lebanon. He said that he was for Hezbollah, 100%. He also said that I would be hard pressed to find anyone in Syria who didn't take Hezbollah's side. He said that many, including himself, had written Hariri off as a Western puppet. I immediately whipped out my camera and showed him the pictures of me in Baalbek, at the gift shop, in the mosque. I told him about my meeting with Abou Yasser and Fatah al-Intifada. He translated for his mother-in-law. She broke into a veritable sunstorm of smiles. Problem solved. I was in. I was one of the family.

We headed for the restaurant, which was situated in the lobby of the Al-Cazino hotel. When we arrived, the room was empty. It was Thursday night, which is Friday night in the Muslim World. We were brought hummus, baba ganoush and salads which were excellent. The meal progressed at a very lackadaisical pace. Sami had insisted that we would drink with him, so while he put away glass after glass of arak, Sam and I had been given a litre of Grant's scotch to deal with.

As we grazed on the excellent meze, Sami told us a little more about himself. He was from the same village as Bashar Assad, the Syrian President, and was also from the same family. They had cousins in common. The way you can tell the members of the Assad family is from their eyes. Only the members of Assad's family from that particular village have blue eyes. All other Syrians have brown eyes. Sami told us that Bashar is a great practical joker and loves a laugh. From the millions of portraits of him glaring down from every available surface in Syria, you'd never have guessed. Sami wanted me to stay in Lattakia and hang out. He told me to forget Damascus. He told me to call my wife and have her fly out. He told me I shouldn't go home. For some reason, I couldn't help but pick up on an undertone of power in his entreaties. This guy wasn't a farmer. When I asked around about him later, people simply shrugged and said that nobody knows what he did, but most likely the secret police. All I know is that he was a flawlessly generous host, an excellent dancer and a very funny guy when drunk, something he claimed he only did one night a week.

Meat arrived on great sizzling platters. Bread, salad and hummus was refilled. We ate until we were fit to burst. The band kicked up a notch and soon the dance floor was filled with young Syrians in trendy clothes, snapping their fingers and strutting their stuff. Sami and his wife cut a rug real nice as well. Grace and I even managed to get Sam in all his Englishness to take to the dance floor and convulse enthusiastically in a close approximation of being in time.

At the end of the evening, the band left, the lights came up and the revellers simply took the instruments from the stage and began playing by themselves, singing and dancing around their tables. I got behind the drum kit and jammed along to a few Syrian folk numbers. When I got up to leave, I noticed that I had been dancing so vigorously in my flip-flops that I had cut my foot in several places and was bleeding quite badly.

Sami dropped Sam, Grace and I back at the hotel and bid us good night. I collapsed into bed, a third of a litre of scotch the worse for wear and dreading the hangover to come.

Day 18: Baalbek/Lattakia, Syria - "I know this is a visa. But you still need a visa."

Captain Libya and Kris left first thing in the morning for Beirut. I enjoyed a wholesome shwarma breakfast and then Mohammed gave me a lift to the bus station. A minibus was headed for the border. At the border I would have to walk into Syria and then get a bus on the Syrian side to Homs, a hub city where I would find a connection to Lattakia.

The ride to the border was uneventful, other than the strange feeling of surfacing for air as we drove up and out of the Bekaa Valley, leaving behind the Shia posters, portraits of Khomeini and Hezbollah flags. I had felt no threat in Baalbek and in fact had been made very welcome by everyone. However, when we were leaving, as the propaganda fell away I just felt as if an oppressive atmosphere was dispersing. No matter how cheerful the people, when you know that their idea of a good time is a Shia state enforcing strict Sharia law where music is illegal and women have to be covered, it colours your discourse with them, even on a subconscious level.

We arrived at the Lebanese border and I got through with very little difficulty. Getting back into Syria was to prove another matter altogether. I was told when leaving Syria that I would be able to re-enter the country from Lebanon even though my visa was only a single-entry. At the border, I waited placidly amidst the chaos of men perched on stacks of building materials shouting and smoking, spilling ashes on me, leaning over me, throwing passports and visa stamps at the officers behind the glass in an attempt to get taken care of first. I got my passport to a chubby, moustachioed guy in uniform who put it to one side. I motioned solicitously to him several times but he had his own system and eventually my passport was opened forty-five minutes later.

Once opened, my passport sat limply in his hand for a further half-hour before he actually looked at it. He flipped through it once, twice, thrice, an increasingly perplexed expression on his face. My heart sank. He looked at me and said something in Arabic. I said I only spoke English. A hunched over priest wearing a beanie and holding a Swiss passport was by my side. I asked him to translate. He Swissed me. A Syrian guy on my other side took up my cause, shouted at the guard, listened, shouted again, listened again and then told me the bad news.

"You need a visa."

"But I have a visa."

The guy said something to the guard. He held out the passport. I flipped to my Syrian visa and pointed at it, saying the word visa over and over. I felt like a character from Quest for Fire or Clan of the Cave Bear. The guard looked at my Syrian visa and then spoke to my impromptu translator. My translator turned to me.

"I know this is a visa. But you still need a visa."

What?

It transpired that my Syrian visa, because it was a single-entry, would not get me back into Syria. I had to go to the bank to buy Syrian money ($52 worth), then go to the visa stamp desk to buy the visa stamps, then come back and have the stamps put into my passport and accredited. I headed for the bank.

The bank was a single room hut about fifty yards from the passport office. A man stood hunched behind filthy glass, chain-smoking. I showed him my passport, said the word visa and then the words "fifty-two dollars". He nodded and held out his hand. I gave him a 50 euro note. He typed on his keyboard, looked at the screen, opened drawers and generally gave me the impression that he was cloning a sheep in there. At the end of the process he handed me 2400 Syrian pounds.

Now, for those of you who, gee whizz, DON'T know the exchange rate, the euro/Syrian rate is 1:70. 50 euro is 3500 Syrian pounds, not 2400. I did a quick sum in my head and figured out the problem. Fuckpants McGee in there had changed my euros at the dollar rate. I waved the wad of Syrian at the glass and demanded more. He looked at me blankly. I spoke in English, he spoke in Arabic. Eventually he called off to one side and a young guy came up to me. He spoke English, albeit with a heavily limited vocabulary.

"Problem?"

I explained.

"No good. Wait."

He spoke rapidly to Fuckpants McGee. Fuckpants shouted in Arabic. I grabbed the calculator and told him to get a fifty dollar and a fifty euro note. He complied. I waved the euro bill and typed in the exchange rate on the calculator. Then I waved the dollar bill and typed in the dollar rate. Then I waved my too-small stack of Syrian money. Then I waved my hands in front of me in the universal gesture for "there you go, bitch, explain that". He clicked his tongue, lit a cigarette and had an idea. He took back the Syrian money and began typing on the keyboard again. The guy who spoke some English invited me into the anteroom to drink tea while we waited. The anteroom was a bare concrete cell with two single beds in it. These guys lived in the bank. I drank tea and waited for the next stage of the negotiations.

After about half an hour in the bank, Fuckpants succeeded in explaining to me that the first exchange was an honest mistake and that he needed to change my euros in two stages, first the exact amount for the visa which would be given to me with one receipt and then the balance, which would come with a separate receipt. This, he explained, was because the visa guy would issue my visa stamp to the amount on the receipt, not an arbitrary amount that I told him. I was gripping my tea glass as hard as I could to avoid hurling it into his benevolently explanatory face. I left, eventually, with two receipts and the right amount of money.

Visa Guy sold me my stamps without a hitch and I was back in the scrum at the passport office within seconds. I found another good-natured Syrian to shout on my behalf and, after filling in another form, waiting another half-hour, gesturing wildly to several men with guns and threatening to slap the Swiss priest in the beanie, I had a valid Syrian visa and was free to re-enter Syria. Kaloo-kallay. It had taken me about two and a half hours.

I got a minibus from the border to the Al-Kadmous bus stop in Homs, a dreadful dusty little outpost with nothing to recommend it other than a mediocre shwarma-teria and exquisite baklava dispensed by a charmingly rotund man with a world-beating combover. Within the hour I was on a bus to Lattakia.

I arrived at the Safwan Hotel in Lattakia like a prodigal son. Mohammed, his crazy uncle and the other characters all gave me hugs and asked after CL and our Lebanese exploits. I sat chatting with them and a few fellow travellers in the reception of the hotel until late. One of the topics, broached by a friend of Mohammed's, a benign but sleazy little number with slightly too-perfect hair, John Lennon glasses and a very cheerfully self-deprecating demeanour, was that of the trend of re-hymenisation in Syria and other Arab countries. Apparently, our little friend was saying, it is very common for Arab girls who want to have sex to have an operation that places a fresh membrane over the vaginal opening where the hymen once was. They have the operation before their wedding and it provides them a stress-free wedding night. Nick, one of the travellers in the reception, added that where he lives in Turkey, it is a very delicate matter because doctors who perform the operation often use their knowledge of the patient's sexual activity to blackmail the girls after they've replaced the hymen. These re-virginised girls have to look long and hard for a doctor that is both willing to perform the operation, which is illegal without parental consent, and trustworthy enough to have sensitive details about the girls without abusing them.

On that note, I decided it was time for me to retreat to my boudoir for a good night's sleep.

The ride to the border was uneventful, other than the strange feeling of surfacing for air as we drove up and out of the Bekaa Valley, leaving behind the Shia posters, portraits of Khomeini and Hezbollah flags. I had felt no threat in Baalbek and in fact had been made very welcome by everyone. However, when we were leaving, as the propaganda fell away I just felt as if an oppressive atmosphere was dispersing. No matter how cheerful the people, when you know that their idea of a good time is a Shia state enforcing strict Sharia law where music is illegal and women have to be covered, it colours your discourse with them, even on a subconscious level.

We arrived at the Lebanese border and I got through with very little difficulty. Getting back into Syria was to prove another matter altogether. I was told when leaving Syria that I would be able to re-enter the country from Lebanon even though my visa was only a single-entry. At the border, I waited placidly amidst the chaos of men perched on stacks of building materials shouting and smoking, spilling ashes on me, leaning over me, throwing passports and visa stamps at the officers behind the glass in an attempt to get taken care of first. I got my passport to a chubby, moustachioed guy in uniform who put it to one side. I motioned solicitously to him several times but he had his own system and eventually my passport was opened forty-five minutes later.

Once opened, my passport sat limply in his hand for a further half-hour before he actually looked at it. He flipped through it once, twice, thrice, an increasingly perplexed expression on his face. My heart sank. He looked at me and said something in Arabic. I said I only spoke English. A hunched over priest wearing a beanie and holding a Swiss passport was by my side. I asked him to translate. He Swissed me. A Syrian guy on my other side took up my cause, shouted at the guard, listened, shouted again, listened again and then told me the bad news.

"You need a visa."

"But I have a visa."

The guy said something to the guard. He held out the passport. I flipped to my Syrian visa and pointed at it, saying the word visa over and over. I felt like a character from Quest for Fire or Clan of the Cave Bear. The guard looked at my Syrian visa and then spoke to my impromptu translator. My translator turned to me.

"I know this is a visa. But you still need a visa."

What?

It transpired that my Syrian visa, because it was a single-entry, would not get me back into Syria. I had to go to the bank to buy Syrian money ($52 worth), then go to the visa stamp desk to buy the visa stamps, then come back and have the stamps put into my passport and accredited. I headed for the bank.

The bank was a single room hut about fifty yards from the passport office. A man stood hunched behind filthy glass, chain-smoking. I showed him my passport, said the word visa and then the words "fifty-two dollars". He nodded and held out his hand. I gave him a 50 euro note. He typed on his keyboard, looked at the screen, opened drawers and generally gave me the impression that he was cloning a sheep in there. At the end of the process he handed me 2400 Syrian pounds.

Now, for those of you who, gee whizz, DON'T know the exchange rate, the euro/Syrian rate is 1:70. 50 euro is 3500 Syrian pounds, not 2400. I did a quick sum in my head and figured out the problem. Fuckpants McGee in there had changed my euros at the dollar rate. I waved the wad of Syrian at the glass and demanded more. He looked at me blankly. I spoke in English, he spoke in Arabic. Eventually he called off to one side and a young guy came up to me. He spoke English, albeit with a heavily limited vocabulary.

"Problem?"

I explained.

"No good. Wait."

He spoke rapidly to Fuckpants McGee. Fuckpants shouted in Arabic. I grabbed the calculator and told him to get a fifty dollar and a fifty euro note. He complied. I waved the euro bill and typed in the exchange rate on the calculator. Then I waved the dollar bill and typed in the dollar rate. Then I waved my too-small stack of Syrian money. Then I waved my hands in front of me in the universal gesture for "there you go, bitch, explain that". He clicked his tongue, lit a cigarette and had an idea. He took back the Syrian money and began typing on the keyboard again. The guy who spoke some English invited me into the anteroom to drink tea while we waited. The anteroom was a bare concrete cell with two single beds in it. These guys lived in the bank. I drank tea and waited for the next stage of the negotiations.

After about half an hour in the bank, Fuckpants succeeded in explaining to me that the first exchange was an honest mistake and that he needed to change my euros in two stages, first the exact amount for the visa which would be given to me with one receipt and then the balance, which would come with a separate receipt. This, he explained, was because the visa guy would issue my visa stamp to the amount on the receipt, not an arbitrary amount that I told him. I was gripping my tea glass as hard as I could to avoid hurling it into his benevolently explanatory face. I left, eventually, with two receipts and the right amount of money.

Visa Guy sold me my stamps without a hitch and I was back in the scrum at the passport office within seconds. I found another good-natured Syrian to shout on my behalf and, after filling in another form, waiting another half-hour, gesturing wildly to several men with guns and threatening to slap the Swiss priest in the beanie, I had a valid Syrian visa and was free to re-enter Syria. Kaloo-kallay. It had taken me about two and a half hours.

I got a minibus from the border to the Al-Kadmous bus stop in Homs, a dreadful dusty little outpost with nothing to recommend it other than a mediocre shwarma-teria and exquisite baklava dispensed by a charmingly rotund man with a world-beating combover. Within the hour I was on a bus to Lattakia.

I arrived at the Safwan Hotel in Lattakia like a prodigal son. Mohammed, his crazy uncle and the other characters all gave me hugs and asked after CL and our Lebanese exploits. I sat chatting with them and a few fellow travellers in the reception of the hotel until late. One of the topics, broached by a friend of Mohammed's, a benign but sleazy little number with slightly too-perfect hair, John Lennon glasses and a very cheerfully self-deprecating demeanour, was that of the trend of re-hymenisation in Syria and other Arab countries. Apparently, our little friend was saying, it is very common for Arab girls who want to have sex to have an operation that places a fresh membrane over the vaginal opening where the hymen once was. They have the operation before their wedding and it provides them a stress-free wedding night. Nick, one of the travellers in the reception, added that where he lives in Turkey, it is a very delicate matter because doctors who perform the operation often use their knowledge of the patient's sexual activity to blackmail the girls after they've replaced the hymen. These re-virginised girls have to look long and hard for a doctor that is both willing to perform the operation, which is illegal without parental consent, and trustworthy enough to have sensitive details about the girls without abusing them.

On that note, I decided it was time for me to retreat to my boudoir for a good night's sleep.

Day 17: Deir Qannoubine/Baalbek - "Hezbollah gave me free batteries!"

The sun woke me up. At my feet lay the valley and the mountain on the other side of it.  I got up, dressed and admired the view from my "bedroom".

I got up, dressed and admired the view from my "bedroom".

The other guys were up and packing their gear. We ate another can of hummus and another can of luncheon meat. Last night had not been an abberation. The breakfast was as abysmal as the dinner. Horror.

We picked our way up the side of the mountain, pressing upwards at an average angle of 60% or so. CL and Kris were in decent shape and pressed on. After the first ten minutes I looked like I had just stepped out of a shower. Absolutely drenched in sweat, I stumbled and wheezed my way up the mountainside. The views were spectacular. The path up the mountain let out into someone's back yard. We paused there to get our breath and drink some water. A man sitting by his garage told us we were 7km from Bcharre. That made sense, since we had left Bcharre to come this way. Now we had to walk back.

The path up the mountain let out into someone's back yard. We paused there to get our breath and drink some water. A man sitting by his garage told us we were 7km from Bcharre. That made sense, since we had left Bcharre to come this way. Now we had to walk back.

We got to the church in the centre of Bcharre town at a touch before 13:00. We made it known that we were headed for Baalbek and after a flurry of negotiations, we had a taxi for LL50,000 (25 euros). There are no bus or minibus services to Baalbek from Bcharre. The taxi ride would take us from Bcharre in the centre of the Kadisha Valley back up to the Cedars and then over the top of the snowy mountains there into the Bekaa Valley. Baalbek is venerated as one of the most ancient cities in the world and has one of the best preserved temples in existence.

After passing the Cedars, the taxi climbed up and up into the clouds. The green of the Kadisha Valley gave way to the brown rocks and dust of the mountains. Driving over the pass between the peaks, the road was lined with snow, sometimes as high as six or seven feet on either side. This road is impassable in winter. The snow that remained ended cleanly at the road where plows had cleared the way for spring traffic. We reached the top of the mountain range that separates the Bekaa and Kadisha Valleys.

This road is impassable in winter. The snow that remained ended cleanly at the road where plows had cleared the way for spring traffic. We reached the top of the mountain range that separates the Bekaa and Kadisha Valleys.  The taxi stopped and we got out to take pictures of the incredible views. The wind was brutal and cold.

The taxi stopped and we got out to take pictures of the incredible views. The wind was brutal and cold.  It has been a steamy 26C in the Kadisha Valley earlier but now, a scant forty-five minute drive away, it was closer to 12C, less with the wind. We were parked at the highest peak. The clouds were level with us and in some places lower. To the right of us were a series of snow-capped peaks wreathed in clouds. The road, lined with snow, stretched away into the distance. The mountainsides were sheer, a dusty orange red and fell away to reveal a seemingly endless expanse of desolate desert, broken only by the occasional lonely homestead. Pictures in hand, we piled back into the cab and proceeded to Baalbek, home of the fabled ruins of old and also the heart of Hezbollah's Shia support base.

It has been a steamy 26C in the Kadisha Valley earlier but now, a scant forty-five minute drive away, it was closer to 12C, less with the wind. We were parked at the highest peak. The clouds were level with us and in some places lower. To the right of us were a series of snow-capped peaks wreathed in clouds. The road, lined with snow, stretched away into the distance. The mountainsides were sheer, a dusty orange red and fell away to reveal a seemingly endless expanse of desolate desert, broken only by the occasional lonely homestead. Pictures in hand, we piled back into the cab and proceeded to Baalbek, home of the fabled ruins of old and also the heart of Hezbollah's Shia support base.

The taxi dropped us outside the ruins. We were immediately set upon by a lone tout offering Hezbollah t-shirts and flags. The town was deserted apart from the locals going about their business. Hotel and cafe owners lounged dispiritedly on the steps of their establishments. Three days before we arrived in Baalbek, the hotels had been full and the shops and cafes were doing a roaring trade. Touts couldn't price their t-shirts and flags high enough and the stream of tourists was gearing up for the always profitable summer season. Now, we were the only game in town.

We dumped our stuff at the Hotel Shouman, run by the sweet-natured but weirdly apologetic Mohammed Shouman. He showed us his booking chart. Like an eraser had been run down the page, all the names ended three days before. He offered us the best room in the hotel with a great view of the ruins. Then he knocked LL3,000 off the price. Three days before he hadn't even had a room going spare. Now he was virtually begging us to stay at his place as opposed to someone else's.

We set off for the ruins. To Captain Libya's chagrin, they are the only ruins in Lebanon that don't offer student discounts. We paid our money and went in. With the exception of the security guard who had brought his kids to work with him, we were the only people there. It was amazing. Legends surrounding the ruins at Baalbek describe their use as anything from temples to Jupiter and Bacchus to altars of blood sacrifice and wild Roman orgies. The disorganisation of the ruins was refreshing. Stones lie where they fell, strewn around the grounds as if by a giant hand. You can walk, climb and sit where you want and whatever the angle, the view is always rewarding and exotic. The remains of the unfinished temple of Jupiter, columns jutting up like ribs, stand in the centre of the complex. Radiating out from there are courtyards, buildings, staircases, hidden passages that dead end in stone corners and the mind-blowing structure that the plaques refer to as a temple of Bacchus. Purportedly used for drinking and orgies in ancient times, then used as a dungeon in the Middle Ages, whatever the purpose or provenance it is a spectacular building. Complete in every way except for the roof and internal furniture, sitting in the centre of the temple was like travelling back in time. The absence of tourists, children and school groups made it all the more pleasurable.

Purportedly used for drinking and orgies in ancient times, then used as a dungeon in the Middle Ages, whatever the purpose or provenance it is a spectacular building. Complete in every way except for the roof and internal furniture, sitting in the centre of the temple was like travelling back in time. The absence of tourists, children and school groups made it all the more pleasurable.

Like the ruins and temples of Egypt, Baalbek is marked with graffiti that provides a kind of historical record all its own. Carvings of names and countries as far back as 1861 add a certain well-tramped cheapness to the ruins that make them more lovable. Somehow, the idea that our generation isn't the first to desecrate works of art with self-referential scribbling is very comforting. Another curiosity is why the graffiti only goes back to 1861 if the ruins have been here for so long. Maybe graffiti was invented in 1861. Who knew?

After finishing our exploration of the ruins, we returned to the hotel where Mohammed was waiting with an offer we simply could not refuse.

"Big stone?" Mohammed asked hopefully, jiggling his car keys enticingly.

CL, Kris and I looked at each other. "What?"

"Big stone," Mohammed elaborated, nodding encouragingly. "Biggest in the world."

There was an awkward pause.

"You want to see? We can take my car."

CL and Kris were still unconvinced but I was all over that like a cheap suit. Moments later we were in Mohammed's ancient Mercedes on our way to see the self-proclaimed Biggest Stone in the World. Upon arriving there, two things became very clear. First, this stone was very, very, very big. Secondly, it seemed a little too small to be the biggest in the world, but the look of pride on Mohammed's face forced me into exaggerated appreciations of its size.

"Wow!" I cried. "That's a big fucking stone!"

Mohammed beamed. I motioned at CL and Kris.

"Yeah," they added, looking at each other and then me. "That's really big. I've never seen a stone that big." etc.

Pictures were taken of each of us in various "hilarious" poses - "lifting" the stone, being "crushed" by the stone. Eventually, even Mohammed's enthusiasm was waning and we pressed on.

On the way back in the car, we spotted a beautiful blue mosque, built in the Shia style most popularly exhibited in Iran. I asked Mohammed if we could have a look. He parked, walked through the gate, spoke to the guards and came back to us. We would be allowed access to the mosque. I asked why we needed special permission. He explained that this was a Hezbollah mosque, built with Iranian funding. The mosque grounds also played host to that most fabled of creatures, the white whale that Captain Libya and I had sought throughout our visit to Lebanon - the Hezbollah Gift Shop. Was it open? You betzler.

Was it open? You betzler.

The mosque was exquisite inside, hung with crystal chandeliers, the light from the setting sun casting tall beams of lights across the thick carpet. The walls and ceilings were a mosaic of coloured tiles and tiny mirrors, giving the entire room a disco ball effect that was quite something. The centre of the room was given over to a shrine that glowed with a green light. In the shrine was a coffin. Mohammed introduced a member of Hezbollah named Ali who explained the coffin to us. The coffin, as far as his limited English could convey, was the coffin of a child martyr and the mosque as a whole was dedicated to the children of Fatima. Later, in Damascus, I would see the same filigreed cage filled with green light, the same draped coffin, the same money strewn over the top, in the Ummayad Mosque.

The centre of the room was given over to a shrine that glowed with a green light. In the shrine was a coffin. Mohammed introduced a member of Hezbollah named Ali who explained the coffin to us. The coffin, as far as his limited English could convey, was the coffin of a child martyr and the mosque as a whole was dedicated to the children of Fatima. Later, in Damascus, I would see the same filigreed cage filled with green light, the same draped coffin, the same money strewn over the top, in the Ummayad Mosque.

Ali walked us around the mosque, pointing out features and answering our questions either in broken English or through Mohammed as an equally bad interpreter. Around Ali's neck was a huge necklace in the shape of a scimitar, inscribed with the name of the Prophet Ali and a prayer in his name. These necklaces are apparently very popular. The Hezbollah Gift Shop sells loads of them.

These necklaces are apparently very popular. The Hezbollah Gift Shop sells loads of them.

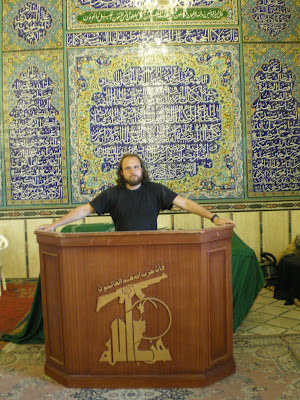

In the corner of the mosque was a pulpit made of plain wood. Embossed onto the front in brass was the Hezbollah logo. We were allowed to pose for photographs behind the pulpit, making various intense facial expressions and gestures, as Ali and Mohammed looked on, bemused. After all of our poses had been committed to digital celluloid for posterity, we repaired to the courtyard where, in the warmth of the dwindling sun, we descended on the Hezbollah Gift Shop like package tourists docking at Aswan in the summer.

After all of our poses had been committed to digital celluloid for posterity, we repaired to the courtyard where, in the warmth of the dwindling sun, we descended on the Hezbollah Gift Shop like package tourists docking at Aswan in the summer.

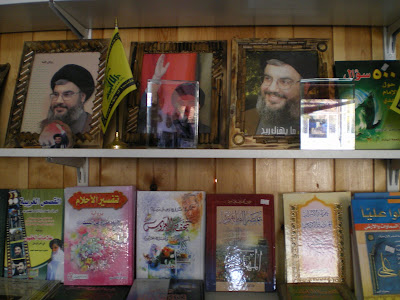

One wall held a DVD rack. DVDs of Hassan Nasrullah (the leader of Hezbollah) giving speeches were side by side with documentaries about the Party of God. Nestled in amongst these more innocuous offerings was a two and a half hour compilation of videos of suicide bombings carried out against Israel. I asked Ali about it. He grinned widely and made a pushing-away gesture with his hands coupled to sound of an explosion.

Nestled in amongst these more innocuous offerings was a two and a half hour compilation of videos of suicide bombings carried out against Israel. I asked Ali about it. He grinned widely and made a pushing-away gesture with his hands coupled to sound of an explosion.

"Yisrael," he grinned. "Boom."

The DVD cost LL40,000, just under 20 euros. Apparently it sells very well but mostly to visiting Arabs and dignitaries. The locals and members of the Hez just watch the re-runs on Al-Manar, the Hezbollah TV channel.

Across from the DVD rack were rows of shelves with stacks and stacks of audio tapes. Being Shia, Hezbollah don't listen to music apart from military marches, so the existence of the tapes fascinated me. I was told that they were speeches by Nasrullah and Khomeini. On the shelf above the tapes were the special brocade hats that Hezbollah members wear, stacked next to Winnie the Pooh and Strawberry Shortcake hats. I pointed at the Pooh hat and looked at Ali askance. He held his hand out, palm down, at waist height and shrugged. You know, for kids.

I pointed at the Pooh hat and looked at Ali askance. He held his hand out, palm down, at waist height and shrugged. You know, for kids.

Books, keyrings, necklaces, tapes, photographs, posters, woodcuts - nothing was beyond the scope of the Hezbollah Gift Shop. This was not a bunch of bearded crazies in the hills with weapons from Iran. These guys have a radio station, a TV station, a merchandising line, a corporate philosophy. To appropriate a Madison Avenue term, they're "sexy".

This was not a bunch of bearded crazies in the hills with weapons from Iran. These guys have a radio station, a TV station, a merchandising line, a corporate philosophy. To appropriate a Madison Avenue term, they're "sexy".

I asked Ali what their bestseller was. He asked to who. I asked him to tell me the best seller to the Shia mosque-goers and the best seller to Hezbollah members. The discerning Shia mosque-goer in Baalbek likes the look of the scimitar necklace inscribed with Ali's name and prayer. They like it equally in silver and in retro woodcut. The Hezbollah member-about-town, on the other hand, fancies a much more prosaic object. The most popular seller to members of Hezbollah is a keyring/mobile phone lanyard that is solar-activated, flashing an image of Nasrullah and the Hezbollah logo when exposed to sunlight. In true globalist fashion, it is also the only product in the gift shop that is not made in Lebanon. It is Made in China.

The attitude that Ali affected once behind the counter was not that of a zealot by any stretch of the imagination, but rather the same approach as any salesman I've ever met. He forced me to try on a hat and then clucked and flapped his hands about how good I look, even taking a picture of me on his phone and showing it to me since there was no mirror to hand. He tried to upsell CL and myself, but in the end only shifted a couple of keyrings. As we took our leave, there were handshakes all round and cheerful waves as we made our way back to the car. On the way out, I noticed a massive mosaic of Khomeini and Khamenei waving to the masses. The backdrop was the Al-Aqsa mosque in Jerusalem. I looked back at the gift shop. Ali stood in the entrance, waving cheerfully. A passing Hezbollah member shook our hands, politely asked where we were from and then gave us some fruit he had just picked.

I looked back at the gift shop. Ali stood in the entrance, waving cheerfully. A passing Hezbollah member shook our hands, politely asked where we were from and then gave us some fruit he had just picked.

We asked Mohammed to drop us a couple of blocks before the hotel so that we could go for a stroll. CL and I wanted to take pictures of the numerous posters and billboards decrying the martyrdom of the Hezbollah Number Two, recently assasinated by the Israelis. I was struck by his resemblance to Omar Bakri, the Syrian citizen recently deported from Britain for exhorting the young Muslim population to become martyrs. There was also a touch of the bearded Alexei Sayle about him.

I was struck by his resemblance to Omar Bakri, the Syrian citizen recently deported from Britain for exhorting the young Muslim population to become martyrs. There was also a touch of the bearded Alexei Sayle about him.

We found a quiet shwarma joint and ate our dinner, surrounded by young men wearing Hezbollah gear, eating and watching the news. When Hariri appeared on the screen, giving a speech denouncing Hezbollah's actions, half the clientele of the shop walked out. On the table, pushed up against the wall, was a small plastic mosque with a slot to donate money to the cause. When you put money in, it played a short burst of the call to prayer. I looked around. There was one on every table.

Night had fallen while we had been eating. On our way back to the hotel, we saw a couple of young girls standing on a street corner. In contrast to all the other women we had seen here in this very religious Shia town, they were clad in tight jeans and strap tops. As we passed by their corner on the other side of the street, a car pulled up and one of them walked to the window. She leaned down, spoke to the driver for a moment and then waved her friend over. They both got in and the car drove off. Now, I'm not saying they were hookers, but...

Captain Libya and I settled down at the hotel to read our books. Kris went out for a brief stroll. He was gone for over an hour. When he got back he was very excited.

"Hezbollah gave me free batteries!" he cried jubilantly.

We enquired as to the provenance of the said boon.

Kris had been walking down the street. A guy came up to him and asked him where he was from. He said Poland. The guy asked him what he did for a living. Kris gave him some answer or other. As the questions continued, more and more guys arrived until Kris realised he was surrounded by thirty or so very stern but friendly guys, some of whom were packing heat. They asked if he had a camera. He replied in the affirmative. They asked if he had taken any pictures in Baalbek. He again said that he had. They asked to see the pictures. Now, wouldn't you know it, but Kris's camera batteries had just died and were back at the hotel charging. The Hezbollah guys went and got him AA batteries. The first set were piss weak and Kris said he wanted proper batteries. The Hezbollah guy apologised and returned a few minutes later with a known brand. They fired up Kris's camera, checked his pictures, gave him back his camera, offered him a soft drink, chatted for a few minutes and disappeared. Kris had burned rubber back to the hotel to share the story.

We talked for a while about how strange it was, this gulf between what these people really did and the way they acted to people they didn't perceive as a threat. It was not necessarily a surprise that they behaved politely, but the level of suspicion was so low as to be almost unnoticeable and as for aggression, we had not been on the receiving end of even a dark glance, let alone a raised voice.

The following day, Kris and CL were off to Beirut. I would be returning to Syria, to Lattakia and from there to Damascus. We dozed off, our heads full of Hezbollah souvenirs, polite gunmen and the possibilities of tomorrow.

The other guys were up and packing their gear. We ate another can of hummus and another can of luncheon meat. Last night had not been an abberation. The breakfast was as abysmal as the dinner. Horror.

We picked our way up the side of the mountain, pressing upwards at an average angle of 60% or so. CL and Kris were in decent shape and pressed on. After the first ten minutes I looked like I had just stepped out of a shower. Absolutely drenched in sweat, I stumbled and wheezed my way up the mountainside. The views were spectacular.

We got to the church in the centre of Bcharre town at a touch before 13:00. We made it known that we were headed for Baalbek and after a flurry of negotiations, we had a taxi for LL50,000 (25 euros). There are no bus or minibus services to Baalbek from Bcharre. The taxi ride would take us from Bcharre in the centre of the Kadisha Valley back up to the Cedars and then over the top of the snowy mountains there into the Bekaa Valley. Baalbek is venerated as one of the most ancient cities in the world and has one of the best preserved temples in existence.

After passing the Cedars, the taxi climbed up and up into the clouds. The green of the Kadisha Valley gave way to the brown rocks and dust of the mountains. Driving over the pass between the peaks, the road was lined with snow, sometimes as high as six or seven feet on either side.

The taxi dropped us outside the ruins. We were immediately set upon by a lone tout offering Hezbollah t-shirts and flags. The town was deserted apart from the locals going about their business. Hotel and cafe owners lounged dispiritedly on the steps of their establishments. Three days before we arrived in Baalbek, the hotels had been full and the shops and cafes were doing a roaring trade. Touts couldn't price their t-shirts and flags high enough and the stream of tourists was gearing up for the always profitable summer season. Now, we were the only game in town.

We dumped our stuff at the Hotel Shouman, run by the sweet-natured but weirdly apologetic Mohammed Shouman. He showed us his booking chart. Like an eraser had been run down the page, all the names ended three days before. He offered us the best room in the hotel with a great view of the ruins. Then he knocked LL3,000 off the price. Three days before he hadn't even had a room going spare. Now he was virtually begging us to stay at his place as opposed to someone else's.

We set off for the ruins. To Captain Libya's chagrin, they are the only ruins in Lebanon that don't offer student discounts. We paid our money and went in. With the exception of the security guard who had brought his kids to work with him, we were the only people there. It was amazing. Legends surrounding the ruins at Baalbek describe their use as anything from temples to Jupiter and Bacchus to altars of blood sacrifice and wild Roman orgies. The disorganisation of the ruins was refreshing. Stones lie where they fell, strewn around the grounds as if by a giant hand. You can walk, climb and sit where you want and whatever the angle, the view is always rewarding and exotic. The remains of the unfinished temple of Jupiter, columns jutting up like ribs, stand in the centre of the complex. Radiating out from there are courtyards, buildings, staircases, hidden passages that dead end in stone corners and the mind-blowing structure that the plaques refer to as a temple of Bacchus.

Like the ruins and temples of Egypt, Baalbek is marked with graffiti that provides a kind of historical record all its own. Carvings of names and countries as far back as 1861 add a certain well-tramped cheapness to the ruins that make them more lovable. Somehow, the idea that our generation isn't the first to desecrate works of art with self-referential scribbling is very comforting. Another curiosity is why the graffiti only goes back to 1861 if the ruins have been here for so long. Maybe graffiti was invented in 1861. Who knew?

After finishing our exploration of the ruins, we returned to the hotel where Mohammed was waiting with an offer we simply could not refuse.

"Big stone?" Mohammed asked hopefully, jiggling his car keys enticingly.

CL, Kris and I looked at each other. "What?"

"Big stone," Mohammed elaborated, nodding encouragingly. "Biggest in the world."

There was an awkward pause.

"You want to see? We can take my car."

CL and Kris were still unconvinced but I was all over that like a cheap suit. Moments later we were in Mohammed's ancient Mercedes on our way to see the self-proclaimed Biggest Stone in the World. Upon arriving there, two things became very clear. First, this stone was very, very, very big. Secondly, it seemed a little too small to be the biggest in the world, but the look of pride on Mohammed's face forced me into exaggerated appreciations of its size.

"Wow!" I cried. "That's a big fucking stone!"

Mohammed beamed. I motioned at CL and Kris.

"Yeah," they added, looking at each other and then me. "That's really big. I've never seen a stone that big." etc.

Pictures were taken of each of us in various "hilarious" poses - "lifting" the stone, being "crushed" by the stone. Eventually, even Mohammed's enthusiasm was waning and we pressed on.

On the way back in the car, we spotted a beautiful blue mosque, built in the Shia style most popularly exhibited in Iran. I asked Mohammed if we could have a look. He parked, walked through the gate, spoke to the guards and came back to us. We would be allowed access to the mosque. I asked why we needed special permission. He explained that this was a Hezbollah mosque, built with Iranian funding. The mosque grounds also played host to that most fabled of creatures, the white whale that Captain Libya and I had sought throughout our visit to Lebanon - the Hezbollah Gift Shop.

The mosque was exquisite inside, hung with crystal chandeliers, the light from the setting sun casting tall beams of lights across the thick carpet. The walls and ceilings were a mosaic of coloured tiles and tiny mirrors, giving the entire room a disco ball effect that was quite something.

Ali walked us around the mosque, pointing out features and answering our questions either in broken English or through Mohammed as an equally bad interpreter. Around Ali's neck was a huge necklace in the shape of a scimitar, inscribed with the name of the Prophet Ali and a prayer in his name.

In the corner of the mosque was a pulpit made of plain wood. Embossed onto the front in brass was the Hezbollah logo. We were allowed to pose for photographs behind the pulpit, making various intense facial expressions and gestures, as Ali and Mohammed looked on, bemused.

One wall held a DVD rack. DVDs of Hassan Nasrullah (the leader of Hezbollah) giving speeches were side by side with documentaries about the Party of God.

"Yisrael," he grinned. "Boom."

The DVD cost LL40,000, just under 20 euros. Apparently it sells very well but mostly to visiting Arabs and dignitaries. The locals and members of the Hez just watch the re-runs on Al-Manar, the Hezbollah TV channel.

Across from the DVD rack were rows of shelves with stacks and stacks of audio tapes. Being Shia, Hezbollah don't listen to music apart from military marches, so the existence of the tapes fascinated me. I was told that they were speeches by Nasrullah and Khomeini. On the shelf above the tapes were the special brocade hats that Hezbollah members wear, stacked next to Winnie the Pooh and Strawberry Shortcake hats.

Books, keyrings, necklaces, tapes, photographs, posters, woodcuts - nothing was beyond the scope of the Hezbollah Gift Shop.

I asked Ali what their bestseller was. He asked to who. I asked him to tell me the best seller to the Shia mosque-goers and the best seller to Hezbollah members. The discerning Shia mosque-goer in Baalbek likes the look of the scimitar necklace inscribed with Ali's name and prayer. They like it equally in silver and in retro woodcut. The Hezbollah member-about-town, on the other hand, fancies a much more prosaic object. The most popular seller to members of Hezbollah is a keyring/mobile phone lanyard that is solar-activated, flashing an image of Nasrullah and the Hezbollah logo when exposed to sunlight. In true globalist fashion, it is also the only product in the gift shop that is not made in Lebanon. It is Made in China.

The attitude that Ali affected once behind the counter was not that of a zealot by any stretch of the imagination, but rather the same approach as any salesman I've ever met. He forced me to try on a hat and then clucked and flapped his hands about how good I look, even taking a picture of me on his phone and showing it to me since there was no mirror to hand. He tried to upsell CL and myself, but in the end only shifted a couple of keyrings. As we took our leave, there were handshakes all round and cheerful waves as we made our way back to the car. On the way out, I noticed a massive mosaic of Khomeini and Khamenei waving to the masses. The backdrop was the Al-Aqsa mosque in Jerusalem.

We asked Mohammed to drop us a couple of blocks before the hotel so that we could go for a stroll. CL and I wanted to take pictures of the numerous posters and billboards decrying the martyrdom of the Hezbollah Number Two, recently assasinated by the Israelis.

We found a quiet shwarma joint and ate our dinner, surrounded by young men wearing Hezbollah gear, eating and watching the news. When Hariri appeared on the screen, giving a speech denouncing Hezbollah's actions, half the clientele of the shop walked out. On the table, pushed up against the wall, was a small plastic mosque with a slot to donate money to the cause. When you put money in, it played a short burst of the call to prayer. I looked around. There was one on every table.

Night had fallen while we had been eating. On our way back to the hotel, we saw a couple of young girls standing on a street corner. In contrast to all the other women we had seen here in this very religious Shia town, they were clad in tight jeans and strap tops. As we passed by their corner on the other side of the street, a car pulled up and one of them walked to the window. She leaned down, spoke to the driver for a moment and then waved her friend over. They both got in and the car drove off. Now, I'm not saying they were hookers, but...

Captain Libya and I settled down at the hotel to read our books. Kris went out for a brief stroll. He was gone for over an hour. When he got back he was very excited.

"Hezbollah gave me free batteries!" he cried jubilantly.

We enquired as to the provenance of the said boon.

Kris had been walking down the street. A guy came up to him and asked him where he was from. He said Poland. The guy asked him what he did for a living. Kris gave him some answer or other. As the questions continued, more and more guys arrived until Kris realised he was surrounded by thirty or so very stern but friendly guys, some of whom were packing heat. They asked if he had a camera. He replied in the affirmative. They asked if he had taken any pictures in Baalbek. He again said that he had. They asked to see the pictures. Now, wouldn't you know it, but Kris's camera batteries had just died and were back at the hotel charging. The Hezbollah guys went and got him AA batteries. The first set were piss weak and Kris said he wanted proper batteries. The Hezbollah guy apologised and returned a few minutes later with a known brand. They fired up Kris's camera, checked his pictures, gave him back his camera, offered him a soft drink, chatted for a few minutes and disappeared. Kris had burned rubber back to the hotel to share the story.

We talked for a while about how strange it was, this gulf between what these people really did and the way they acted to people they didn't perceive as a threat. It was not necessarily a surprise that they behaved politely, but the level of suspicion was so low as to be almost unnoticeable and as for aggression, we had not been on the receiving end of even a dark glance, let alone a raised voice.

The following day, Kris and CL were off to Beirut. I would be returning to Syria, to Lattakia and from there to Damascus. We dozed off, our heads full of Hezbollah souvenirs, polite gunmen and the possibilities of tomorrow.

Day 16: Tripoli/Bcharre/Deir Qannoubine - The Monastery Monastery

Another night at the Pension Haddad, another mile of my poor skin destroyed by marauding mosquitoes. CL, Kris and I were up and on the road bright and early. We found the minibus to Bcharre and rode out the three hours enjoying the increasingly dramatic scenery. The bus rolled to a stop outside a military installation. We were the only people left on board apart from the driver.

"Ici Les Cedres," he told me in French, since we had earlier established that this was the easiest way to communicate.

"But we asked for Bcharre," I said in French.

"But I thought you wanted the Cedars."

And so it came to pass that our voyage to the Kadisha Valley began with an unplanned visit to the Cedars, the last forest of cedar trees in Lebanon, followed by a 4km hike back down the road to Bcharre.

The Cedars is a beautiful forest, according to the French inscription literally called The Forest of the Cedars of God. At the centre of the very modest stand of cedar trees is a dead tree into whose larger branches the bodies of people have been sculpted. In the crux of the tree, a figure that looks suspiciously like Jesus appears to be crucified.  Down the other side of the hill, the forest disappears abruptly and there is an incredible panorama of snow-covered mountains and rolling rocky hills.

Down the other side of the hill, the forest disappears abruptly and there is an incredible panorama of snow-covered mountains and rolling rocky hills.  CL hiked off to take pictures of the snow. I sat on a rock and looked at the hills, breathing in the smells of the flowers and listening to the grumbling of the insects.

CL hiked off to take pictures of the snow. I sat on a rock and looked at the hills, breathing in the smells of the flowers and listening to the grumbling of the insects.

We hiked back to Bcharre with a little help from a guy who let us ride in the back of his pickup truck for about one and a half kilometres. We enjoyed a burger lunch at the local cafe and then, provisioned with appetising cans of luncheon meat and hummus, we set off for the valley floor.

The path to the Kadisha Valley floor from Bcharre town is supposed to run down the back of the church. We followed this path and, after climbing down a very steep path that wound between houses built into the cliff face, we came to a dead end. A lady leaned out of her window and shouted directions. We could walk all the way back up the incline (ugh) or we could cut through her neighbour's orchard in order to get to the path. Her neighbour, she said, "probably wouldn't shoot us". Awesome.

We cut through the orchard, pausing now and again to enjoy the views. The orchard ended at a small stream that ran down the side of the mountain.  There were two paths, one across it and one up the rocks and around the top. A small man carrying a large box motioned to us that he was going down to the valley and we should cut across the stream. Now, when you are in a remote part of a country apparently teetering on the brink of civil war and you find yourself at a junction, looking for a way down a mountain, I challenge you to find a better source of directions than a small man carrying a large box. Who doesn't speak English. Or, from later inspection, any other recognisable language. We followed Small Large Box Man down the path and then, being more accustomed to the descent than us, he disappeared round a corner. As I took the bend in my stride, I came to a halt. The path ahead of us, the one and only path down the mountainside, was approximately one and a half feet wide. Very narrow indeed. When leading strangers down a mountainside along a narrow path, there are many things that would occur to the average person to do. Offer them water. Make polite conversation. Show worn photos of toothless wife and mugging grandkids. However, Small Large Box Man, in a fit of what can only be described as Fear Factor genius, had dumped his large box squarely onto the path. Hovering above it and to either side were hundreds of bees. The box had contained bees. Now there were bees everywhere and I had to walk through them. SLBM motioned for me to walk by as if it were the most natural thing in the world.

There were two paths, one across it and one up the rocks and around the top. A small man carrying a large box motioned to us that he was going down to the valley and we should cut across the stream. Now, when you are in a remote part of a country apparently teetering on the brink of civil war and you find yourself at a junction, looking for a way down a mountain, I challenge you to find a better source of directions than a small man carrying a large box. Who doesn't speak English. Or, from later inspection, any other recognisable language. We followed Small Large Box Man down the path and then, being more accustomed to the descent than us, he disappeared round a corner. As I took the bend in my stride, I came to a halt. The path ahead of us, the one and only path down the mountainside, was approximately one and a half feet wide. Very narrow indeed. When leading strangers down a mountainside along a narrow path, there are many things that would occur to the average person to do. Offer them water. Make polite conversation. Show worn photos of toothless wife and mugging grandkids. However, Small Large Box Man, in a fit of what can only be described as Fear Factor genius, had dumped his large box squarely onto the path. Hovering above it and to either side were hundreds of bees. The box had contained bees. Now there were bees everywhere and I had to walk through them. SLBM motioned for me to walk by as if it were the most natural thing in the world.  CL, Kris and I braved the bee gauntlet and continued our walk down the mountainside none the worse for wear.

CL, Kris and I braved the bee gauntlet and continued our walk down the mountainside none the worse for wear.

The Kadisha Valley is an exquisitely beautiful place. Not really a traditional valley but more of a gorge, the valley is formed by a deep, verdant chasm between two mountains. The valley floor and mountainsides are teeming with vegetation. Along the valley floor there is a dirt track negotiable by 4x4, leading between obscure houses and an incredibly pointless restaurant. The attractions of the Kadisha Valley are the scenery, the isolation and the monasteries. Several monasteries are built into the rock walls of the valley. Our destination was Deir Qannoubine, a monastery approximately 7km through the valley from the bottom of the Bcharre path. Deir Qannoubine is very special for many reasons, but to me the exquisiteness of its name is unrivalled by its other features. Qannoubine means Monastery. It is literally named Monastery Monastery, or, to give it the full nomenclature, Our Lady of the Monastery Monastery. It is said to be a functioning convent, which makes its double naming as a monastery even funnier.

Several hours and pints of sweat later, we reached Deir Qannoubine. About two-thirds up the rock wall of the valley, the monastery looks out over the valley to stunning effect, taking in the forests, houses, crags and waterfalls. The monastery was abandoned. A candle burning in the chapel meant that someone had been there recently, but we could find no person in residence. Kris and CL put up a tent to sleep in. I opted to sleep on the observation deck under the stars, a choice that I would not regret. I briefly flirted with the idea of sleeping in the chapel, but the chapel was colder than the deck and also had a creepy Evil Dead vibe that I didn't fancy braving.

We got a fire started and broke open our cans of "food". Tinned hummus and luncheon meat may have sounded good when we were in town, but the reality was horrific. The luncheon meat was particularly bad, but the hummus was a revelation of despair. It glooped out of the can in dry chunks and tasted like mashed potato soaked in vinegar. Beautiful.  We sat around the fire, drank tea, choked down our "food" and bedded down for the night.

We sat around the fire, drank tea, choked down our "food" and bedded down for the night.

Lying on the observation deck, looking at the stars, the wind ruffling my hair, the heat of the day not yet gone, it was again impossible to imagine that somewhere on the other side of this great beauty and silence people were firing guns at each other. It's easy to think of conflicts as remote when you are in a different country or continent, but when you are in the same country, maybe three or four hours drive from the heart of the action, and all you can hear is the whistle of the wind and the creaking of the crickets, it really drives home the fact that violence is not as all-encompassing as the media would have us believe. People shooting in Beirut did not equal hordes of armed crazies running amok on every patch of land in the country. The moon was gibbous and hung bright and close. The stars were above my head, my feet touching the edge of the deck beneath which was a sheer drop to the valley floor. Not a shout, an explosion, a single shot could be heard. The loudest thing out here was my breathing and the Polish muttering of CL and Kris in their tent fifty yards away.

I drifted off to sleep. The strange silence that only religious buildings can produce enveloped me. Somewhere at the back of my mind, I expected blood-hungry undead nuns to burst from the cellars and devour us for trespassing. They never did.

Saturday 24 May 2008

Day 15: Tripoli/Batroun/Beddui Refugee Camp - The Intifada loves ping pong

CL and I got up fairly early. Today was to be the day we went to Bcharre, the mountain village from which we would hike through the Kadisha Valley, spend the night and then continue on the Baalbek. We were accompanied by Kris, a Polish guy we had met at the Pension Haddad. What we had not counted on was that the area of Lebanon we were in is Christian. Today was Sunday. There were no buses to Bcharre from Tripoli. Bukra, we were told over and over again. Tomorrow.

We heard that there might be a bus from Batroun to Bcharre, so we hopped a minibus to Batroun and were again confounded by the lack of transport. One taxi driver wanted LL100,000 to drive us to Bcharre. 50 euros. Insanity. Captain Libya went off in search of oranges. Kris and I stayed with the rucksacks and made conversation with a flamboyantly camp hairdresser named Jacques. Jacques was Lebanese and lisped manfully from beneath a meticulously groomed beard. He told us about the nightclubs in Batroun and Beirut. His vote went to a club called Acid, a notorious venue where the $20 entry price also includes free drinks all night. It also regularly gets busted for excessive quantities of gayness. It was Jacques who, while tittering gaily at the thought of it, told CL and me that the beach we had skinny-dipped at was a local gay hotspot. When I said that that explained the watchful guys on the shore, Jacques erupted into peels of laughter, squeezed my arm and called me honey. He gave me his number and told me to come see him at his salon for a haircut. I asked him where his salon was. In Casablanca, Morocco. It's called Jacques. Genius.